In the cherry blossom’s shade

there’s no such thing

as a stranger.

We do not know what hospitality is.

Not yet.

Not yet, but will we ever know?

In the cherry blossom’s shade

there’s no such thing

as a stranger.

We do not know what hospitality is.

Not yet.

Not yet, but will we ever know?

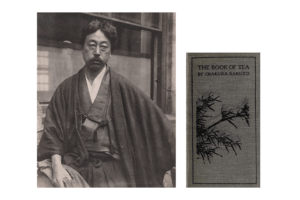

Beyond the difficulties of addressing a culture foreign to one’s own, further difficulties arise from the attempt to write about something that is defined in large part by remaining unspoken. In The Book of Tea, the turn-of-the-century essay that would do so much to change western impressions of Japan, Okakura Kakuzō wondered if perhaps he was betraying his own ignorance of the Japanese ceremony by being so outspoken about it. I am about to betray mine.

I am going to sketch some ideas around the concept of omotenashi: the spirit of welcome, an ambiguous term with ancient roots in Japanese culture. It is a subtle practice that issues from tacit understanding and is ordered around evanescent gestures. For it to be omotenashi, it should be invisible. It should never come across as a performance; hence the term, which, formed by the words omote [おもて, public face] and nashi [なし, nothing] means something like “no mask.” Essential to the concept is a non-hierarchical relationship between host and guests, who each respond to much more than what is spoken, participating together in a spontaneous reciprocal choreography.

I believe that omotenashi, as a gestural and spatial practice, is best considered as a subset of Japanese aesthetics. And here we come upon a further difficulty, for, as the scholar Donald Keene put it, “almost any general statement made about Japanese aesthetics can easily be disputed and even disproved by citing well-known contrary examples.” And yet there seems to be a silhouette here worth describing.

“The Japanese tea masters […] expressing the deep influence of Zen and the more ancient Taoism, developed a cult of devotion to the aesthetics of the ordinary — not only, or even especially, the great chiaroscuro, symphony or cathedral, but the elegance, say, of the broom with which you sweep away the daily dust.”

In Japan, aesthetic development diverged in two significant ways from the western model. In Europe, beginning in the eighteenth century, the philosophical inquiry of aesthetics formalized a theory of the beautiful and its effects. But it took for its primary focus the extraordinary experience, that which is exceptional and rare, and as such planted its gaze squarely on fine arts, that class of objects that are art and art only. The Japanese tea masters, in contrast, expressing the deep influence of Zen and the more ancient Taoism, developed a cult of devotion to the aesthetics of the ordinary — not only, or even especially, the great chiaroscuro, symphony or cathedral, but the elegance, say, of the broom with which you sweep away the daily dust. The ordinary, of course, is ubiquitous, and thus aesthetic development became a democratic pursuit in Japan. “Perfection is everywhere if we only choose to recognise it,” wrote Kakuzō. The paper screen, the well-inked page, the prevailing precision of gesture — these everyday elements could be elevated through conscious attention into objects of intense aesthetic appreciation. Rather than locking aesthetics within the fortified precincts of great museums, and rather than making it dependent on wealth and specialisms, the Japanese found that they could cultivate beauty in every utilitarian object, in every home and hour. This is the sensibility the novelist Junichirō Tanizaki eulogized in In Praise of Shadows, celebrating the ancestors’ way of “making poetry of everything in their lives.”

The second difference is that, for reasons both historical and mysterious, aesthetics came to occupy the place in Japan that religion held in the life of European nations. This is the thesis of the cultural critic Kāto Shūichi, who writes that during its long period of inwardness, “Japanese culture became structured with its aesthetic values at the center. Aesthetic concerns often prevailed even over religious beliefs and duties.” While in Italy Michelangelo was reporting to the Pope, in Kyoto the tea master Sen no Rikyū was imparting philosophical lessons to the Nichijin leaders. In Japan, writes Shūichi, “the art was not illustrating a religion, but a religion becoming an art.” (The distinction has a temporal orientation to it as well, since, as Kakuzō notes: “In religion, the Future is behind us. In art, the present is the eternal.”)

Taken together, these differences begin to draw the contours of a culture for which commonplace aesthetic choices bear a profound significance that western societies can scarcely imagine. Kakuzō, the philosopher of tea, explains the genealogy of this ethos: “Taoism furnished the basis for aesthetic ideals, Zen made them practical.” The practical discipline of Zen then suffused the culture of Japan, structuring the sense of grace of every secular art and domain. In this land where poetry is scripture, the everyday aesthetics of tea, dress, and yes, even such things as transportation and hospitality, are not merely ornamental or functional; they carry the full momentum of ethical realisation in traditional Japan.

In fact the roots of omotenashi may be found in tea — or rather teaism, as Kakuzō described it: “Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence,” he wrote in 1906. Here again is the salvific value of a beverage, a ritual, a routine flash of beauty. All this fussing over tea is in fact “a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.” Tea masters became the clergy of the sublime, furnishing standards of taste in everything from porcelain to flower arrangement, poetry to garden design — all the things we think of when we call to mind Japanese taste. Even today, “Japanese culture exemplifies how moral virtue such as respect for others can be embodied in an aesthetic,” says Yuriko Saito, professor emeritus at the Rhode Island School of Design.

“Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence […] a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.”

Omotenashi is a practice of observation and care that requires an attentiveness that is uncommon, a meditation all on its own. Through this observation — almost worship — of small objects, small gestures, small things, the host creates a state of heightened awareness into which she draws the other. As an expression of Japanese aesthetics, omotenashi both reflects and cultivates an ethic of awareness and everyday beauty that is the moral ideal.

Where omotenashi is practiced, the host waits on the guest with all five senses, using powers of deduction and an almost clairvoyant sensitivity to anticipate what the guest may require before any need is expressed. The host does not seek appreciation or any other thing in return from guests, but rather delights in the rapport and the depth of ease experienced by the guest the further it develops — relishing what Kakuzō called “the mystery of mutual charity.” A tip would ruin the effect. There is no self-abasement in this devotion to the other either; rather, the practitioner of omotenashi is elevated by the inherent dignity of their skill in reading mere suggestion and offering elegant responses. (This is like the Irish poet John O’Dohonue said: when we approach with reverence, great things approach us.)

“By declining opulence, the tea master was able to produce an experience that served to make apparent the things that humans easily forget: that elegance can be experienced in equality, beauty created from simplicity, and abundance found in poverty.”

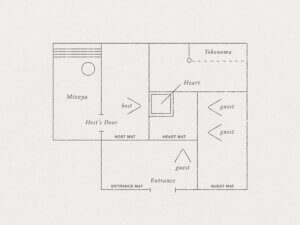

Sen no Rikyū, widely considered one of the greatest aesthetes Japan has produced, remade the tea ceremony in the sixteenth century, establishing forms that have endured to this day. From Rikyū, the ritual emerged in substantially altered dimensions. In creating the first independent tea room, setting it aside from the main architecture of the dwelling, he innovated the size today considered typical: four and a half tatami mats, no more. He made the entrance to the tea room unusually low, requiring even samurai lords to bow as they entered. He championed rough, hand-moulded tea bowls over the Chinese ceramics privileged by his daimyo overlords, seeing in their humility a beauty surpassing that of symmetry and polish. And for the decor of the tokonoma, rejecting a glazed vase, he went out to find a perfect segment of bamboo in which to place a solitary sprig of flowers. In this sparse, intimately crafted space, Rikyū waited on his disciples and guests with rapt devotion.

By declining opulence, the tea master was able to produce an experience that served to make apparent the things that humans easily forget: that elegance can be experienced in equality, beauty created from simplicity, and abundance found in poverty. In fact wabi, the term most closely associated with Japanese aesthetics, is etymologically linked to words for dejection and squalor. That a sense of supreme beauty was extracted from the experience of poverty is a testament to the virtuosity of the Buddhist operation. There is a freedom to wabi, since, as Donald Richie observed in his Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics, “poverty and loneliness could be seen as a liberation from strivings to become rich and popular.”

“If you are over the top, if, say, you open the door to the bathroom for guests, you’re only creating more barriers,“ says Joe Lewis-White, who leads tea service at Slowness. He is part of the team thinking through how to adapt Rikyū’s values and their expression in omotenashi to Flussbad, the Slowness campus in Berlin. Even at a distance of five centuries and nine thousand kilometres, generosity and naturalness must still converge in just measure to put both guests and hosts at ease. “It’s about, how do you welcome people at home? It sounds basic, but that’s all it is. You’ll take someone’s coat when they come in, but you’ll sometimes let them pour their own wine.”

Reflecting on hospitality as a professional artform, Lewis-White says: “In a world that is increasingly difficult, that’s increasingly expensive, increasingly polarized, increasingly lived in points of extreme in every walk of life, the ability to touch six hundred people’s days for the better, that’s a powerful position to be in. In what other job do you get to say you did that?”

“In a world that is increasingly difficult, that’s increasingly expensive, increasingly polarized, increasingly lived in points of extreme in every walk of life, the ability to touch six hundred people’s days for the better, that’s a powerful position to be in. ”

This extreme of thoughtfulness, the wide wings of an imagination of care, can be elicited by a phrase that is likewise traced back to Rikyū: ichigo ichie, meaning literally one time, one meeting. As a mantra, it serves to strip a situation of the cobwebs that can creep up on it from overfamiliarity. Steeped as they are in the notion of impermanence, the sensibility of mono no aware, the Japanese are perhaps more awake than most to the certainty that everything is dying, either quickly or slowly. But even Rikyū could use the invocation of ichigo ichie to condense that knowledge into the vivid instant — hello! If this is truly a once in a lifetime encounter, if this is the last tea ceremony, the last cup of tea we will ever drink together, then let us truly drink it.

The practice of welcome is simply one of the necessary arts of being in the world. (Kakuzō uses just those words in his book, and curiously, Heidegger is alleged to have lifted his famous idiom being-in-the-world from Kakuzō after being handed a copy of Das Buch vom Tee by a Japanese pupil.) Omotenashi is what makes the encounter with the other tolerable. And what is life but one extended encounter with the other.

Both east and west, we are languishing in an epidemic of ugliness. Japan holds clues that lead out of this dessert, but not without some irony. The nation that perfected omotenashi has itself largely abandoned tea for coffee. In the realm of the coffee rush, the future is the religion; the eternal now grows vaguer and vaguer. But in this haze, something stirs. “Young people are yearning to slow down, returning to tea,” says Gene Krell, longstanding editor at Japanese Vogue. In seeking out more patient rituals, they are tilting towards a mode of approach that widens and clarifies attention. Omotenashi’s boon is the reminder that in that threshold in which we encounter one another is a wide open field, one we can plant with beauty. And beauty, some of us suppose, is not so incidental. “Genius is the activity that repairs the decay of things,” wrote Emerson.

But I doubt Rikyū would approve of quite so much exposition. After all, life is short. And hey — look out the window. The cherries are in blossom, and the water is boiling.