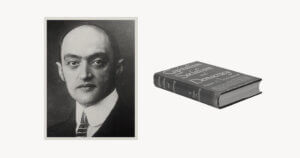

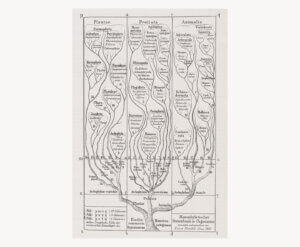

In 1942, Schumpeter published the book that gave us the term “creative destruction.” Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy became one of the twentieth century’s most seminal works of nonfiction. In the vision it lays out, shorter business cycles are nested within Kondratieff’s long waves. While many establishment economists had dismissed Kondratieff’s theory as mystical nonsense, Schumpeter could see the deep pattern too. For Schumpeter, Kondratieff had described something profound: the heartbeat of capitalism, driven not by invisible hands or rational actors but by the disruptive force of entrepreneurial ingenuity that periodically remade entire societies.

Schumpeter’s view of economics was Darwinian, seeing the market as a living, breathing organism that constantly adapts through bursts of technological revolution — inhale! — followed by periods of consolidation and eventual contraction — release. For Schumpeter, the fits and starts were a feature, not a bug. The waves proposed by Kondratieff followed an internal logic that linked them: each wave created the conditions for its own decline as technologies matured and investment opportunities became exhausted, creating a vacuum that begged to be filled by a new wave of innovation. This suggested capitalism had a kind of evolutionary metabolism, periodically shedding old industries to make room for new ones — an idea that was heretical to Soviet economic thinking but welcome in Schumpeter’s liberal America.

The metamorphosis of machines

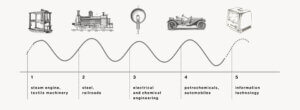

Take the first wave, the start of which Kondratieff located around 1780 with the creation of James Watt’s steam engine and Edward Cartwright’s power loom. These combined technologies revolutionized the textile industry and birthed a new kind of manufacturing. Hitherto agricultural societies were flung one by one into the industrial age. As Britain’s cotton processing increased by orders of magnitude, people moved into cities and filled factories, upending medieval social structures that had held for centuries. But the factories of the time were mostly small, and the means of transportation — horse-drawn carriages and dirt roads — did not allow for goods to be efficiently transported over long distances. Once local demand for textile goods was saturated, a great recession unfolded, leaving millions unemployed and plunged into landless poverty.

The next wave of capitalism would need to find a way out of the rubble of the first. The key innovation Kondratieff identified for his second wave was the steel converter Henry Bessemer perfected in 1855. While steel was known in antiquity, Bessemer’s process allowed large quantities of steel to be produced cheaply. This affordability ushered in a range of new applications for the fortified alloy: crucially steel railways, but also steel ships, steel bridges, steel machines, even steel weapons. With this, the limits to growth that had drawn the first wave to a close were reinterpreted. Transportation was revolutionized by trains, setting off another boom of economic activity. The societies that rode the second wave enjoyed full employment and Victorian optimism. Factory workers gained power through unions and socialist parties, prompting capitalist concessions in the form of the first major social reforms of modernity and the first coming of welfare. Another wave had remade the world.

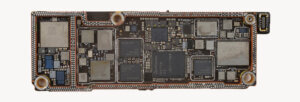

Economists have identified three more K-waves, as they are now known. The third wave was driven by the explosion of electrical and chemical industries, epitomized in the image of towns and cities lighting up at night or the gas masks in the trenches of the Great War. In the fourth wave, the invention of the automobile simultaneously created the urgency to build cars, build roads, and pump oil, giving rise to the most emblematic companies of the mid-twentieth century. The oil crisis of 1973 provided the epitaph for their dominance; something else was brewing in the bowels of Silicon Valley. Innovations such as the personal computer, the world wide web, and the smartphone would power the fifth wave, giving rise to the companies that would outstrip even the petroleum dinosaurs in power: Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon.

These are the masters of the current age of man.