I.

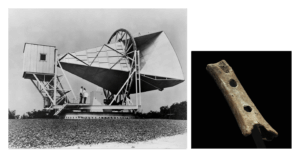

1964, Holmdel, New Jersey.

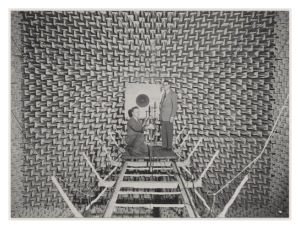

Two radio astronomers at Bell Labs had tried everything to get rid of a hissing rumble in the large horn antenna they had built to receive signals from satellites. They suppressed heat interference in their supersensitive receiver, using liquid helium to cool it within 4° of absolute zero. They removed two pigeons that had nested in the antenna’s throat. Then they cleaned out their droppings. Still the burr persisted like the sound of a distant rainstorm falling on a billion densely packed leaves. The sound was the same no matter what part of the sky they pointed their antenna at, forcing them to conclude that it couldn’t come from the Sun, or the Earth, or even from the center of the Milky Way. Something far vaster was humming.

As it turned out, it was a radio signal from the birth of everything, “radiation left over from an explosion that filled the universe at the beginning of its existence,” a droning telegram that continues to arrive in an unbroken sheet, the reception of which earned those two scientists a Nobel Prize. The accidental discovery of cosmic background radiation confirmed the Big Bang theory of cosmic genesis. The big blast of origin endowed the universe with a bed of buzzing in which everything lays: the sidereal whisper.

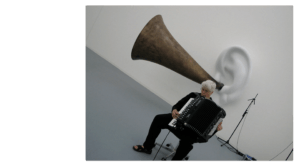

c. 60,000 BCE, Divje Babe Cave, Slovenia.

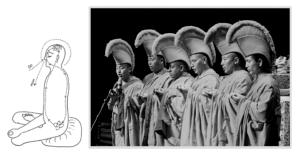

An ancestor sat in a cave, holding the femur of a bear cub firmly between her knees. Using a sharp stone, she carved perfect, circular holes into the shaft of the bone, perfectly spaced to produce a diatonic scale. Bringing it to her lips, she blew, like a creator god blowing over the surface of the deep. In an instant, the bone filled with resonant air, holding a sustained vibration that juddered through her fingers and up her arms, through her body and off the walls of the cave, making her start. The flute was excavated by Slovenia’s Institute of Archaeology in 1995. It is the oldest extant instrument known to science.