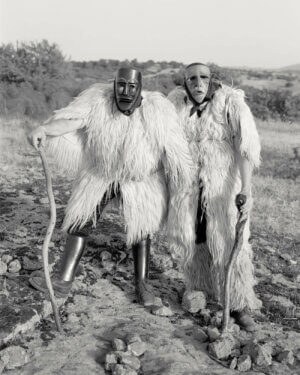

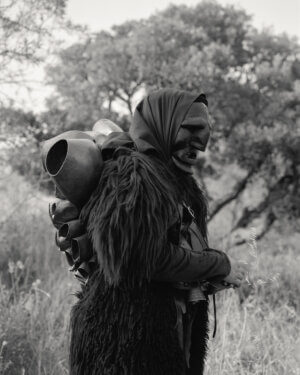

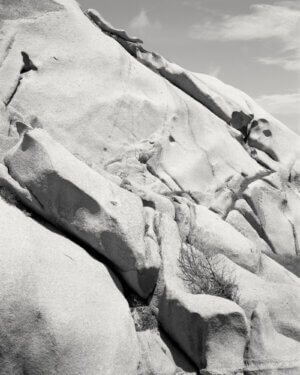

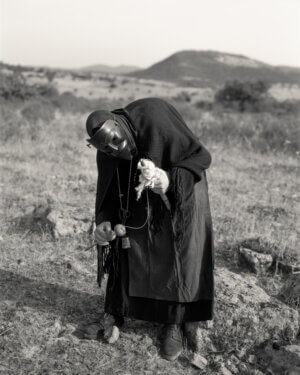

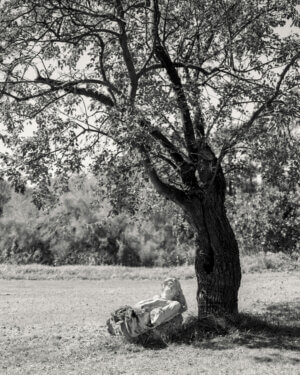

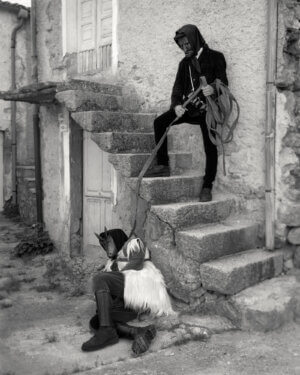

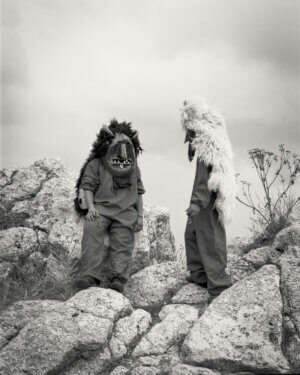

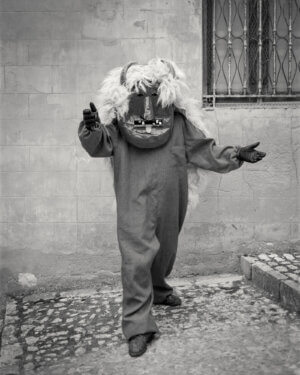

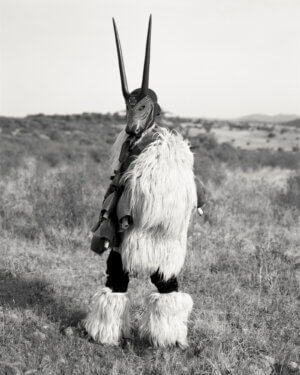

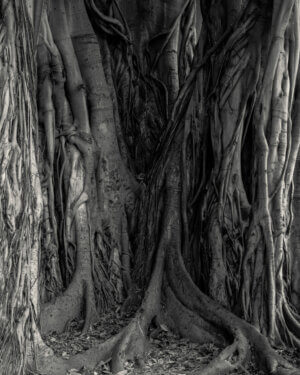

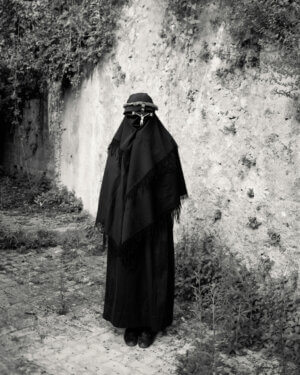

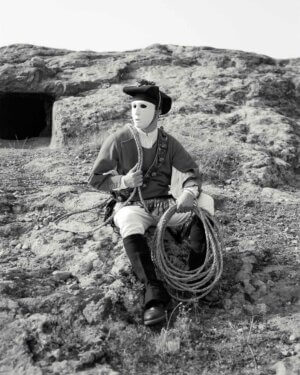

What does pilgrimage mean today? Fascinated by this question, Alys Tomlinson documents enduring religious and cultural rites across her stunning photographic oeuvre. Shooting in large format and using vintage techniques, Tomlinson slows down the photographic process, embedding within a context in order to know it. Across acclaimed series such as Ex-Voto (2019), Lost Summer (2020) and most recently, Gli Isolani (The Islanders) (2022), she captures – in formal portraiture, detailed still lifes, and emotive landscapes – timeless human devotion to rituals that celebrate cultural heritage and spiritual growth.

This month, Tomlinson is a featured artist at CABIN, a new art space founded by Slowness creative director Lawrence Hazen and photography editor José Cuevas. Located in Kreuzberg off the Landwehr Canal, CABIN hosts rotating exhibitions of visual art and design, a curated shop of editioned works and independent art books, as well as a dedicated space for performance, video and sound art.

CABIN’s inaugural exhibition At the Edge of Everything, included works from Tomlinson’s series Gli Isolani (The Islanders), documenting striking rural folk traditions in Italy.

Following the show’s opening, we caught up with Tomlinson to reflect on the potency of her anthropological approach to photography.