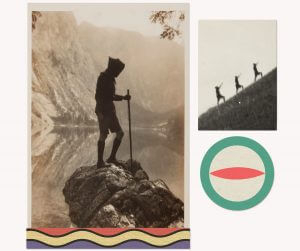

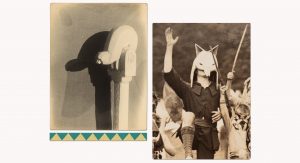

THEY MARCH IN FORMATION through the British landscape in faded photographs wearing strange, hooded costumes that evoke ancient rites and rituals. They stand solitary on hilltops raising arms to an unseen deity before a haunted, empty pastoral tableau. They kneel at the foot of Stonehenge and strike androgynous poses, their young, healthy bodies draped in wild cloaks and futuristic tabards bearing skulls and wolves like some modernist interpretation of Celtic and Egyptian mythology. Is this an ancient sect? A contemporary fashion shoot? A cult? Are these faux-weathered images of the psychedelic denizens of a present-day music festival?

The photos depict The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, an obscure but ambitious organization founded in 1920 by the charismatic artist and writer John Hargrave as a splinter group from the Boy Scout movement. Initially conceived as a coeducational pacifist youth organization for the promotion of woodcraft and camping, Kibbo Kift would go on to pursue a dizzying range of interests, including health and handicraft, myth and propaganda, magic and spirituality, education and economics, protest and design.