Within the Cave You Understand the History

ch. IIIWithin the Cave You Understand the History

Serra da Arrábida, Setúbal

ch. III >

>

“Within the cave, you understand the history,” said Rui, a kind-eyed man in his 40s with the strong, wiry physique and sun-weathered skin of someone who spends their days scaling rockfaces. We met him at a café in the tiny village of Aldaia de Meco, not far from where Slow is transforming an immense piece of depleted coastal agricultural land into a working farmstead for yearlong living and hospitality. We followed him toward the Arrábida coast, then parked our cars at the edge of a precipitously sloping sea of vegetation leading down to a cluster of caves where Rui made the discovery of his life in 2009.

He was working at the time as an official government speleologist, tasked with helping to create an archeological map of the municipality of Sesimbra. One day, while exploring in the caves, he reached out and felt something unusual sticking out of a crack in the wall.

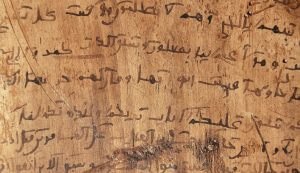

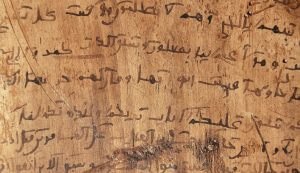

“The texture felt strange, so I grabbed it and started pulling and pulling, and then I saw the Arabic writing,” said Rui. “I couldn’t believe my eyes.” He was holding an 850-year-old wooden tablet covered in Koranic scripture, preserved by the unique microclimate of the cave, the salty ocean air and wind-breaking southern orientation.

Archeologists knew that during the Islamic period, the caves of Arrábida were used as a lookout point to watch for invading Vikings and pirates, but Rui’s discovery proved there had been a madrasa in the caves. The tablet was hidden there in or around 1165, the year the Moorish Sesimbra Castle was taken by the Portuguese Reconquista.

“They were inside the madrasa,” said Rui. “And then when they saw the Portuguese coming, they had to hide it in the cave, so that the scriptures would not fall into the hands of the Catholics, the infidels. So they hid it, thinking they would recover it afterwards, but they didn't know that the Portuguese would take over and they would never be back. It sat there hidden for a thousand years—until I found it.”

We followed Rui down through the coastal brush, Jurassic limestone cliffs rising up beside us as we descended. The Atlantic stretched out in brilliant deep cerulean blue. Finally, we reached the caves, climbing up into the cool, dark interior. Gazing out, it was easy to imagine what it might have been like hundreds, thousands, even millions of years ago, taking shelter here, watching out for attackers, sending prayers out across the open ocean.

Through his work in the Arrábida, Rui told us, he’s helping to preserve the history and culture of the area, something that was neglected for many years. Particularly the Moorish period, from the 8th century, when Muslims sailed from North Africa and took control of what is now Portugal and Spain, until it was retaken in the 13th century by Catholic crusaders, was for many years glossed over or painted as a brutal occupation.

But recently, a new generation of Portuguese is rediscovering its Muslim past, taking a new look at the 500-year period when Portugal was known as al-Andalus, a prosperous kingdom of the Umayyad Empire that left its imprint not only in Arabic-derived place names like Algarve, Alentejo and Alfama but in Portuguese craft traditions, architectural styles, religious rituals and literary tropes. It’s a recasting of history that Rui’s work in the caves has helped to deepen.

“I do this so that we don’t forget, so that we remember our own story,” said Rui, looking out from the mouth of the cave toward the curving geomorphic coastline. “Not the story of Portugal but the human story. Because in my heart I’m not Portuguese. I’m a man, I’m a caver, and I’m a citizen of the world.”

Within the Cave You Understand the History

Serra da Arrábida, Setúbal ch. III“Within the cave, you understand the history,” said Rui, a kind-eyed man in his 40s with the strong, wiry physique and sun-weathered skin of someone who spends their days scaling rockfaces. We met him at a café in the tiny village of Aldaia de Meco, not far from where Slow is transforming an immense piece of depleted coastal agricultural land into a working farmstead for yearlong living and hospitality. We followed him toward the Arrábida coast, then parked our cars at the edge of a precipitously sloping sea of vegetation leading down to a cluster of caves where Rui made the discovery of his life in 2009.

He was working at the time as an official government speleologist, tasked with helping to create an archeological map of the municipality of Sesimbra. One day, while exploring in the caves, he reached out and felt something unusual sticking out of a crack in the wall.

“The texture felt strange, so I grabbed it and started pulling and pulling, and then I saw the Arabic writing,” said Rui. “I couldn’t believe my eyes.” He was holding an 850-year-old wooden tablet covered in Koranic scripture, preserved by the unique microclimate of the cave, the salty ocean air and wind-breaking southern orientation.

Archeologists knew that during the Islamic period, the caves of Arrábida were used as a lookout point to watch for invading Vikings and pirates, but Rui’s discovery proved there had been a madrasa in the caves. The tablet was hidden there in or around 1165, the year the Moorish Sesimbra Castle was taken by the Portuguese Reconquista.

“They were inside the madrasa,” said Rui. “And then when they saw the Portuguese coming, they had to hide it in the cave, so that the scriptures would not fall into the hands of the Catholics, the infidels. So they hid it, thinking they would recover it afterwards, but they didn't know that the Portuguese would take over and they would never be back. It sat there hidden for a thousand years—until I found it.”

We followed Rui down through the coastal brush, Jurassic limestone cliffs rising up beside us as we descended. The Atlantic stretched out in brilliant deep cerulean blue. Finally, we reached the caves, climbing up into the cool, dark interior. Gazing out, it was easy to imagine what it might have been like hundreds, thousands, even millions of years ago, taking shelter here, watching out for attackers, sending prayers out across the open ocean.

Through his work in the Arrábida, Rui told us, he’s helping to preserve the history and culture of the area, something that was neglected for many years. Particularly the Moorish period, from the 8th century, when Muslims sailed from North Africa and took control of what is now Portugal and Spain, until it was retaken in the 13th century by Catholic crusaders, was for many years glossed over or painted as a brutal occupation.

But recently, a new generation of Portuguese is rediscovering its Muslim past, taking a new look at the 500-year period when Portugal was known as al-Andalus, a prosperous kingdom of the Umayyad Empire that left its imprint not only in Arabic-derived place names like Algarve, Alentejo and Alfama but in Portuguese craft traditions, architectural styles, religious rituals and literary tropes. It’s a recasting of history that Rui’s work in the caves has helped to deepen.

“I do this so that we don’t forget, so that we remember our own story,” said Rui, looking out from the mouth of the cave toward the curving geomorphic coastline. “Not the story of Portugal but the human story. Because in my heart I’m not Portuguese. I’m a man, I’m a caver, and I’m a citizen of the world.”

10317 Berlin, Germany

1100-383 Lisbon, Portugal