It’s hard to imagine Tulum as it was just a few decades ago: a sleepy seaside village on an otherwise empty stretch of staggeringly beautiful coastline, nothing but thick jungle and white sand lapped by bright blue Caribbean waters. The few visitors who came slept in hammocks strung between palm trees and watched in a psilocybin haze as a big white Yucatán moon rose above the pyramidal ruins of the last great Mayan city. It began with the backpackers, then the off-grid hippies, downtown artists and would-be mystics. Soon Tulum had become known as a sun-drenched New Age paradise, where travelers could turn on, tune in, drop out—or all of the above. Developers took note, buying up the coast and peppering it with newly built “eco-resorts,” hotels and bars with ever-bigger sound systems. Before long, the beach had gone mainstream.

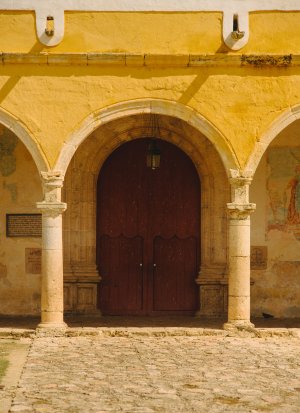

But like the Marrakesh Medina or South Beach in the ’80s, today’s Tulum is a place of chaos, contradiction and potential. Dig beneath the surface and you’ll find the old magic remains. It’s also a perfect jumping-off point for a road trip up the Yucatán Peninsula, an enigmatic stretch of Mexico where underground caves, Mayan ruins, tropical jungle and taffy-colored colonial towns lie in wait to be explored.