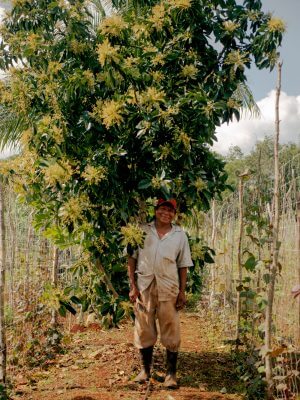

SLIGHTLY MORE THAN 66 MILLION YEARS AGO a meteorite plunged towards Earth and struck ground just at the edge of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, causing a ricochet of destruction across the globe that is widely considered to have led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. This catastrophic event is evidenced in the many sinkholes, or cenotes, found beneath the ground in vast areas of the Yucatán. These majestic cenotes were deeply spiritual places for the ancient Maya, who believed them to be entrances to the underworld, but they drained water and nutrients from the earth, making agriculture problematic. In order to get the most out of the soil, the Maya used a “milpa” system, which involves the rotation of crops, each feeding nutrients into the soil for the crop to follow. The land was periodically rested to allow it to regenerate, a practice that required patience and lots of space.

Over the past decades, as populations and food demands have risen and climate change has made the growing season less predictable, these traditional systems have fallen to the wayside, replaced by the socially and environmentally destructive methods of the industrial agriculture sector. The introduction of agrochemicals and genetically modified organisms mean that farmers have to pay for new seeds (as the GMO seeds do not replant well) and sell their produce to large agribusiness companies who buy it at low prices to sell at a profit. This top-down system means that farmers often are left with little money to feed their own families—let alone to feed them with the healthy produce for which the region is known.

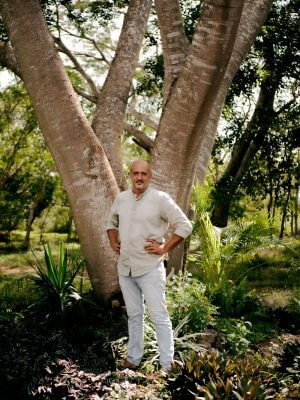

But now a growing regenerative agriculture movement across the region is aiming to combat some of these issues, bringing back sustainable farming methods and providing nutritious sustenance to local communities. “The biggest problem was a dietary one,” said Gonzalo Samaranch Granados, a former journalist who in 2015 co-founded Meztiza de Indias, a 200-acre farm in Valladolid that aims to counteract the harmful effects of Mexico’s agrochemical industry.