When Rudolf Steiner was nine years old he had what he believed to be his first psychic vision. His aunt appeared to him in a state of crisis, begging for his help. At the time, neither Steiner nor his family knew that she had, in fact, recently died in a far-off town. This 1870 occurrence was proof to a young Steiner that he had made contact with a realm beyond everyday physical reality. And what many might eventually have dismissed as a commonplace childhood experience steeped in coincidence was, for him, the catalyst for a lifelong quest to understand our spiritual world—one that would profoundly shape the coming century.

From organic grocery stores and biodynamic agriculture to alternative education and buildings without perpendicular angles, it’s hard to travel far these days without stumbling over some trace of Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian philosopher and esotericist whose pioneering approaches to understanding the human body and our connection to the world permeate society today. From his teens until his death in 1925, Steiner was the very definition of a multihyphenate. He bridged the worlds of philosophy and occult with mathematics and science to create a comprehensive, holistic outlook and approach to understanding life that would eventually amass devout followers around the world.

Steiner was born in 1861 in a tiny village within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was a telegraph operator who worked for the Southern Austria railway, and the family moved frequently. An intellectually gifted and introverted child, Steiner enjoyed mathematics and, after the vision of his aunt, continued to have what he later described as clairvoyant episodes. By age 15, he claimed to fully understand the concept of time, and at 21, he had a pivotal (though chance) encounter with an herb gatherer who conveyed a knowledge of nature that was spiritual and non-academic, cementing his spiritual interests even further.

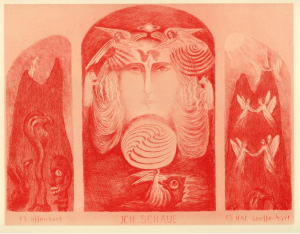

After studying in Vienna, he was commissioned to edit the works of German literary titan Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He fell deeply into Goethe’s world, moving, in 1888, to Weimar to work as an editor at the Goethe archives. It was at this point that Steiner began to philosophize the merging of our sensory reality with a parallel spiritual reality through a committed process of inner observation and meditative thought. He outlined this idea in the seminal work Philosophy of Freedom (1894), noting that “the experience of thinking, rightly understood, is in fact an experience of spirit.”

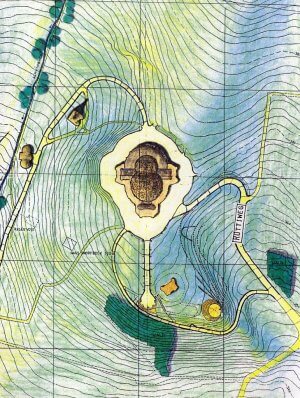

With the right training, he thought, anyone could develop the ability to experience the spiritual world, including the higher nature of oneself and others—and, in turn, become more moral, creative, and free as an individual. He adopted the term “anthroposophy” for his system of thought, blending anthropo (human) with sophia (wisdom) and in 1913, founded the Anthroposophical Society.