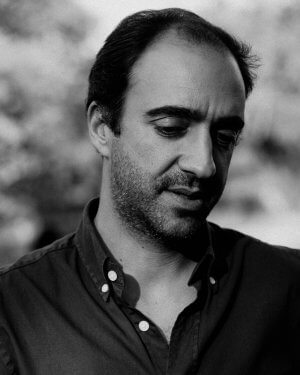

FIVE YEARS AGO Lisbon native João Rodrigues had attained the kind of success as a chef that others only dream of, earning numerous awards and a string of Michelin stars for Feitoria Restaurant at Altis Belém Hotel. And yet something, he felt, wasn’t right.

“I started to question what I was doing. We had products from all around the world, very good products, but it was lacking some identity,” said João. “I was thinking that when someone travels to Portugal, they want to know what Portuguese people eat and what is the culture, you know, because food is culture.”

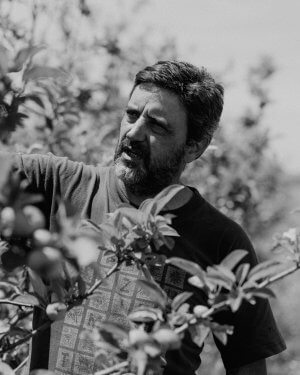

Authentic food culture, João realized, must begin with the ingredients, so he began calling chefs all around the country and asking them for recommendations of farmers, divers, fishermen and other local producers whose products and methods were very local, cultural, traditional, who did things “the old way.” He began visiting all these producers to try to understand their processes, their challenges and difficulties.