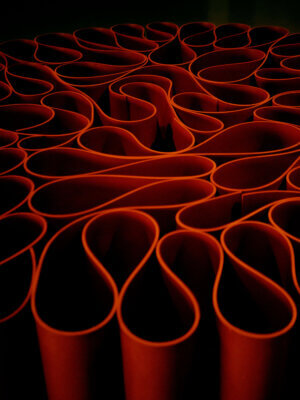

While Maika is away, Renee is overseeing production on the piece they’re creating for the New York exhibition, a table made of rawhide in a deft reimagining of a material more commonly used for drumheads, lassos and whips. “The conventional way of using this material is for it to be oiled so that it would be flexible,” said Maika. ”But it can also be a very, very hard material—and it keeps its organic qualities. You can still see some of the veins of the animal, some of the pores. It works almost as a thermal plastic, because you can mold it, let it dry, and it will harden and keep that shape.”

“It’s a very primitive material used since the paleolithic to make housing. It has a long and interesting history,” said Maika, adding that rawhide has been used both as a torture device, by wrapping people’s arms in the material and letting it dry until it shrinks and twists their bones, and as a way to heal broken bones. To make the table, they stitched two rawhides together and let them dry over a mold they’ve created. “You have to attend the rawhide almost 24/7 in its drying process,” said Maika, who spends hours every day on the phone with Renee consulting about production. “It’s very easy, for example, for the sutures to rip apart. And you have to hydrate it in places where the moisture is evaporating quicker than in others. It’s almost like caring for a living creature.”

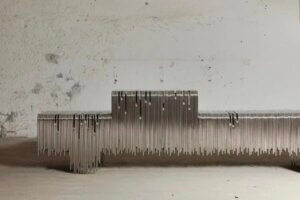

Other pieces in production include a wax alarm clock and what looks like two giant metal hooks covered in metallic barnacles, like some kind of menacing claw from a mechanical dystopia. “Back in summer I was visiting a chroming workshop in Mexico City, and I just noticed these hooks that are used to submerge pieces that are going to be plated—like car parts, into chrome vats,” said Maika. “They look like coral structures almost, like something that has been like at the bottom of the ocean forgotten for centuries, or maybe an ocean on Venus.”

Maika rescued the hooks, which were going to be discarded, and she and Renee started experimenting. They hope to make a chair—or maybe candle holders. But whatever they create, it will be something functional, that people actually live with—because it’s this that drew Maika to design in the first place. “I was frustrated with like exhibition modality in which the objects are things that stay almost dissected in a museum or in an exhibition and there is no co-living with them,” said Maika. “I was interested in the potential for these objects of use that respond in a way that, for example, a painting wouldn’t. There is more of an intimate level of interaction.”